Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license.Licence.

Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license.Licence.

Introduction

Bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—which occurs when changes in bacteria cause the drugs used to treat infections to become less effective—has emerged as one of the leading public health threats of the 21st century. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, commissioned by the UK Government, argued that AMR could kill 10 million people per year by 2050.1, 2 Although these forecasts have been criticised by some,3, 4 WHO and numerous other groups and researchers agree that the spread of AMR is an urgent issue requiring a global, coordinated action plan to address.5, 6, 7, 8 Information about the current magnitude of the burden of bacterial AMR, trends in different parts of the world, and the leading pathogen–drug combinations contributing to bacterial AMR burden is crucial. If left unchecked, the spread of AMR could make many bacterial pathogens much more lethal in the future than they are today.

One major challenge to tackling AMR is understanding the true burden of resistance, particularly in locations where surveillance is minimal and data are sparse. Extensive literature exists estimating the effects of AMR on incidence, deaths, hospital length of stay, and health-care costs for select pathogen–drug combinations in specific locations,1, 2, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12 but, to our knowledge, no comprehensive estimates covering all locations and a broad range of pathogens and pathogen–drug combinations have ever been published. For instance, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a 2019 report on AMR infections and deaths in the USA for 18 AMR threats using surveillance data,6 while Cassini and colleagues10 estimated the burden of eight bacterial pathogens and 16 pathogen–drug combinations in the EU and European Economic Area for 2007–15. Likewise, Lim and colleagues estimated the burden of multidrug resistance in six bacterial pathogens in Thailand in 2010,11 and Temkin and colleagues estimated the incidence of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems in 193 countries in 2014.12

Although these publications are important contributions to the body of work on AMR, they are insufficient to understand the global burden of AMR and identify and target the highest priority pathogens in different locations. Additionally, existing studies have generally considered only one measure of AMR burden.13 Because we do not know the extent to which drug-resistant infections would be replaced by susceptible infections or by no infection in a scenario in which all drug resistance was eliminated, it is important to quantify the burden on the basis of both these counterfactual scenarios.

In this study, we present the first global estimates of the burden of bacterial AMR covering an extensive set of pathogens and pathogen–drug combinations using consistent methods for both counterfactual scenarios.

Methods

Overview

We developed an approach for estimating the burden of AMR that makes use of all available data and builds on death and incidence estimates for different underlying conditions from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019, which provides age-specific and sex-specific estimates of disease burden for 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories in 1990–2019.14 Our approach can be divided into ten estimation steps that occur within five broad modelling components (a flowchart of the estimation steps is given in the appendix p 123). First, we obtained data from multiple data sources, including from published studies (eg, microbiology data, inpatient data, data on multiple causes of death, and pharmaceutical sales data) and directly from collaborators on the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance project,15 members of the GBD Collaborator Network, and other data providers.

We estimated the disease burdens associated with and attributable to AMR for 12 major infectious syndromes (lower respiratory infections and all related infections in the thorax; bloodstream infections; peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections; meningitis and other bacterial CNS infections; typhoid, paratyphoid, and invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella spp; urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis; diarrhoea; tuberculosis [not including tuberculosis associated with HIV]; bacterial infections of the skin and subcutaneous systems; endocarditis and other cardiac infections; infections of bones, joints, and related organs; and gonorrhoea and chlamydia) and one residual category, 23 bacterial pathogens, 18 drug categories or combinations of drugs for which there is resistance, and 88 pathogen–drug combinations (appendix pp 45–46). We modelled all-age and age-specific deaths and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 204 countries and territories, and we present aggregated estimates for 21 GBD regions, seven GBD super-regions, and globally in 2019 (a full list of GBD locations by region is available in the appendix pp 100–05).16

For the first counterfactual scenario—where all drug-resistant infections are replaced by susceptible infections—we estimated only deaths and DALYs directly attributable to resistance. For the second counterfactual scenario—where all drug-resistant infections are replaced by no infection—we estimated all deaths and DALYs associated with resistant infection. Estimates of AMR burden based on each counterfactual are useful in different ways for informing the development of potential intervention strategies to control AMR.13, 17, 18

Input data

We used several data collection strategies. Through our large collaborator networks, we obtained datasets not previously available for AMR research, including hospital and laboratory data, as well as datasets published previously and those outlined in research articles.19 Each component of the estimation process had different data requirements and, as such, the input data used for each modelling component differed. The diverse data sought included the following sources: pharmaceutical companies that run surveillance networks, diagnostic laboratories, and clinical trial data; high-quality data from researchers including large multisite research collaborations, smaller studies, clinical trials, and well established research institutes based in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs); data from public and private hospitals and public health institutes providing diagnostic testing; global surveillance networks; enhanced surveillance systems; national surveillance systems; and surveillance systems for specific organisms such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (all sources are listed by data type in the appendix pp 8–15).

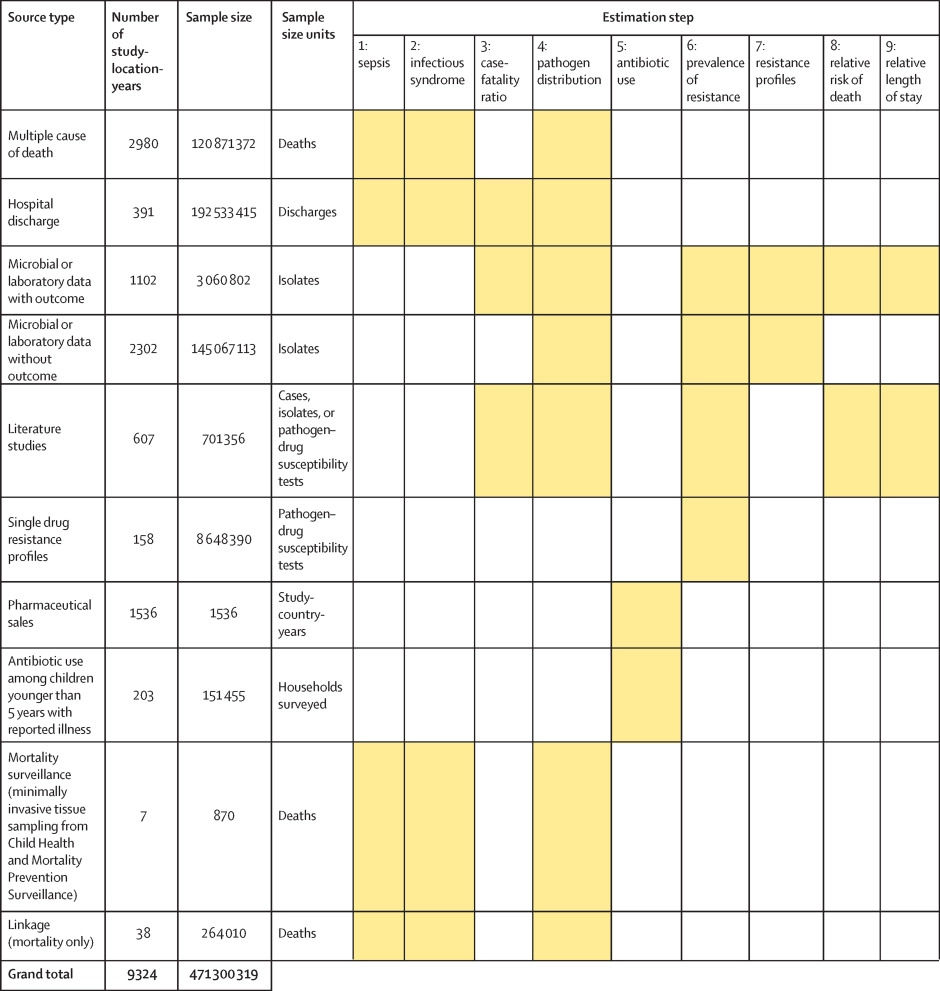

Figure 1 shows a summary of the distinct data types gathered and for which estimation step each data type was used. Also shown in figure 1 is the number of unique study-location-years and individual records or isolates available for each data type. Location-years of data refer to unique GBD locations and years for which we have records or isolates. In total, 471 million individual records or isolates covering 7585 study-location-years were used as input data to the estimation process. Table 1 shows the number of individual records or isolates used and number of countries covered in each of the five broad modelling components separately by GBD region. Two of five components included data from every GBD region and two of five included data from 19 of 21 GBD regions. Our models of sepsis and infectious syndrome were the most geographically sparse, covering 16 countries from ten regions; the input data for these models were highly detailed microdata that are only sparsely available. However, our framework for estimating the total envelope of infectious syndrome mortality used GBD cause-specific mortality estimates to minimise reliance on these sparse data.

Figure 1: Data inputs by source type

Total sample size for each source type, regardless of specific inclusion criteria for a given estimation step. Individual isolates that were tested multiple times for resistance to different antibiotics are listed only once here whenever isolates were identified uniquely in the data. For datasets where isolates could not be uniquely identified across pathogen–drug combinations, such as some antimicrobial resistance surveillance systems, some isolates might be double counted. Yellow boxes indicate that the source type was used in that estimation step. A full list of data sources included in this study, organised by data type, is included in the appendix (pp 8–15).

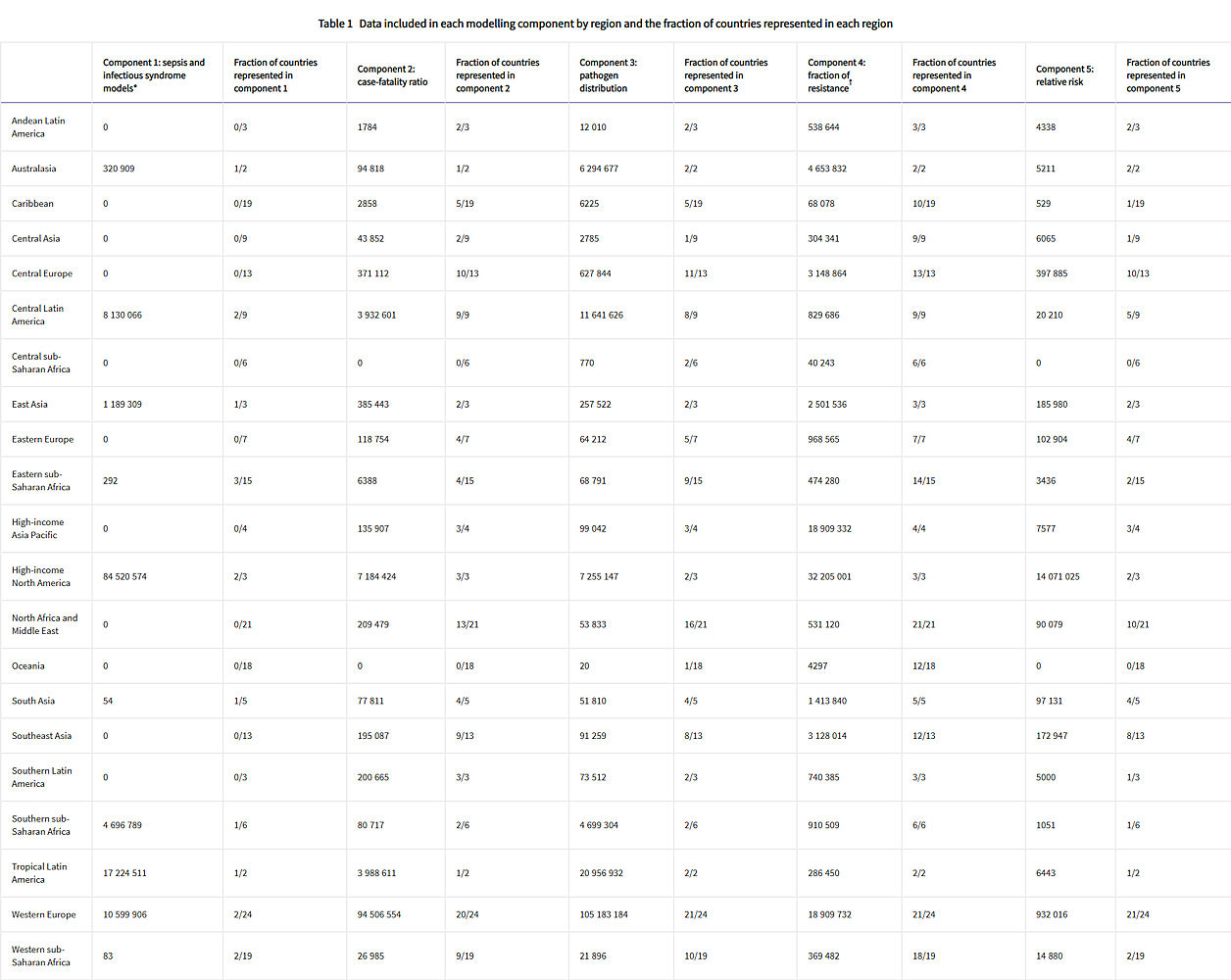

Table 1: Data included in each modelling component by region and the fraction of countries represented in each region

Total sample size and fraction of countries covered for each modelling component by GBD region. The units for sample size are deaths for sepsis and infectious syndrome models; cases for case-fatality ratios; cases, deaths, or isolates for pathogen distribution; pathogen–drug tests for fraction of resistance; and pathogen–drug tests for relative risk. Sample sizes reflect model-specific selection criteria, resulting in lower totals for the sepsis, infectious syndrome, case-fatality ratio, and pathogen distribution models in this table than those in figure 1. Totals for fraction of resistance and relative risk are higher in this table than in figure 1 because of the difference in units for certain source types, such as microbial data (isolates in figure 1, pathogen–drug tests here). Several data sources inform multiple components; therefore, data points should not be summed across a row as that will lead to duplication. More information on the data types used and the components that they inform is presented in the appendix (pp 8–15). GBD=Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study.

* The data points listed in the sepsis and infectious syndrome models include only sources used to determine the fraction of sepsis in non-communicable diseases; maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases; and injuries, as well as the distribution of infectious syndromes; final estimates of the number of deaths in each infectious syndrome were generated by multiplying the fractions of sepsis and infection syndromes on GBD 2019 death estimates; GBD 2019 death estimates include 7417 sources with 28 106 location-years of data for under-5 mortality and 7355 sources with over 7322 location-years of data.

† For sources in the fraction of resistance modelling component, de-duplication across antibiotic resistance tests was not possible, leading to potential double counting, as seen in the high-income Asia Pacific region.

All data inputs for the models were empirical data, not modelled estimates, except for a custom meta-analysis of vaccine probe data that we did to estimate the fraction of pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (appendix pp 37–38). All study-level covariates for models, such as age and sex, were extracted from empirical data. All country-level covariates were modelled estimates that were produced previously for GBD 2019,20, 21 or those that were modelled by Browne and colleagues.22

Results: Deaths Directly Attributable to Antibacterial Resistance

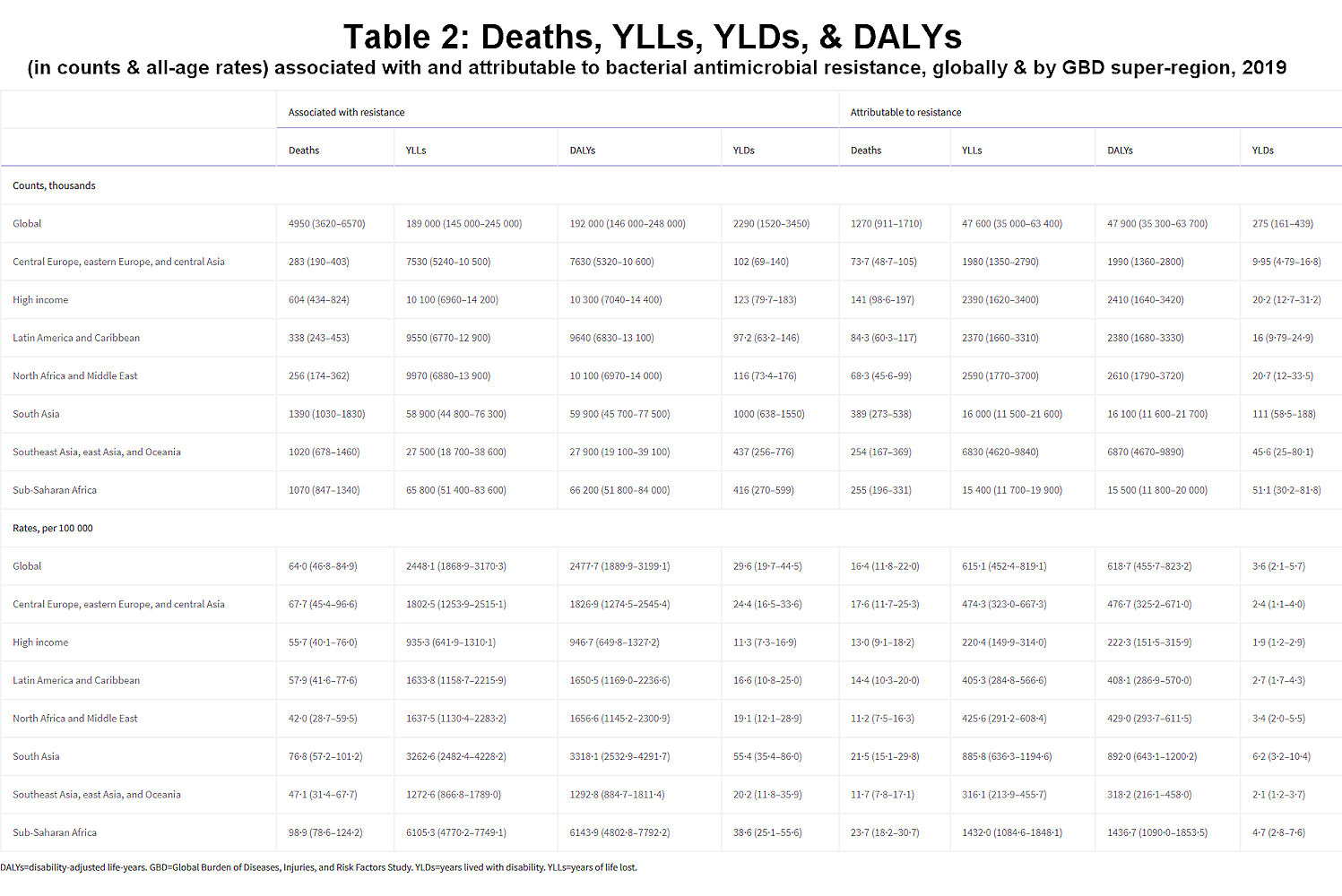

We estimated that, in 2019, 1·27 million deaths (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 0·911–1·71) were directly attributable to resistance (ie, based on the counterfactual scenario that drug-resistant infections were instead drug susceptible) in the 88 pathogen–drug combinations evaluated in this study. On the basis of a counterfactual scenario of no infection, we estimated that 4·95 million deaths (3·62–6·57) were associated with bacterial AMR globally in 2019 (including those directly attributable to AMR). Table 2 provides estimates of deaths, YLLs, and DALYs from AMR for each counterfactual.

Table 2Deaths, YLLs, YLDs, and DALYs (in counts and all-age rates) associated with and attributable to bacterial antimicrobial resistance, globally and by GBD super-region, 2019

DALYs=disability-adjusted life-years. GBD=Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study. YLDs=years lived with disability. YLLs=years of life lost.

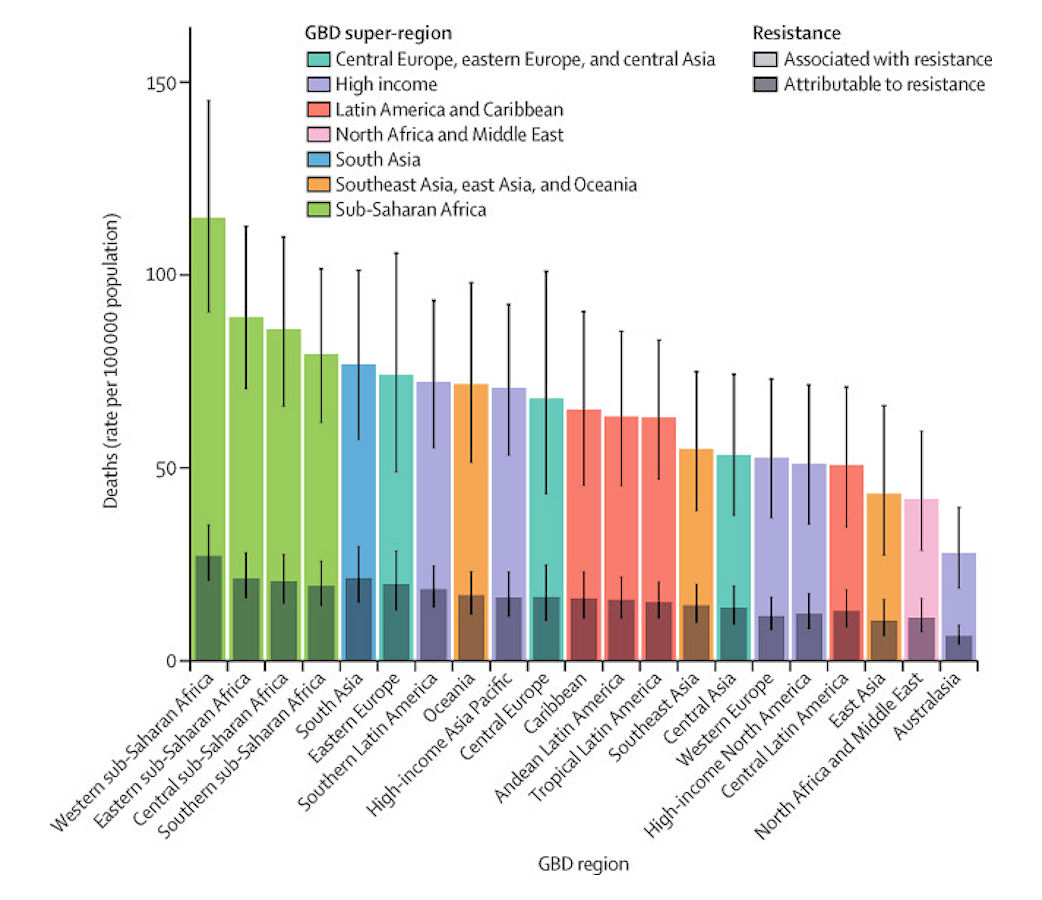

We estimated that among the 21 GBD regions, Australasia had the lowest AMR burden in 2019, with 6·5 deaths per 100 000 (95% UI 4·3–9·4) attributable to AMR and 28·0 deaths per 100 000 (18·8–39·9) associated with AMR in 2019 (figure 2). Western sub-Saharan Africa had the highest burden, with 27·3 deaths per 100 000 (20·9–35·3) attributable to AMR and 114·8 deaths per 100 000 (90·4–145·3) associated with AMR. Five regions had all-age death rates associated with bacterial AMR higher than 75 per 100 000: all four regions of sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia. Although sub-Saharan Africa had the highest all-age death rate attributable to and associated with AMR, the percentage of all infectious deaths attributable to AMR was lowest in this super-region (appendix p 97).

Figure 2: All-age rate of deaths attributable to and associated with bacterial antimicrobial resistance by GBD region, 2019

Estimates were aggregated across drugs, accounting for the co-occurrence of resistance to multiple drugs. Error bars show 95% uncertainty intervals. GBD=Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study.

Natureza Patents New Antibiotic Agents

Natureza’s patented formulations introduce a transformative new class of antibiotic agents that overcome bacterial resistance and removes the time barrier of investment return.

Natureza’s research offers a true paradigm shift, one that would remove the imbalance in development cost by eliminating the ability of bacteria to become resistant. With the promise of new drugs being able to be marketed for years providing not only the time to recover investment, but a profit as well, a new investment environment would emerge that would encourage the development of new, much needed antibiotics.

[su_patentstatement]

Lack of New Antibiotics Threatens Global Efforts to Contain Drug-Resistant Infections

“Never has the threat of antimicrobial resistance been more immediate and the need for solutions more urgent,” says Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of WHO.